Meet the locals

Home to more threatened species than anywhere else in the country the animals and plants of Te Manahuna are tough. Rare birds and lizards, insects that can freeze without dying, and stunted mountain plants that are some of the strangest and lovliest natives you can find.

BIRDS

Ngutu pare / Wrybill

Population

5000

Conservation Status

Threatened – nationally increasing

How are we protecting them?

Ngutu pare/wrybill are benefiting from our increased braided river predator control.

No other bird in the world has a curved bill, and the wrybill’s always curves to the right. The shape of the bill allows them to probe for insects under river stones – and mayfly larvae are their particular favourite.

Ngutu pare breed on the braided riverbeds of the South Island, and then migrate north for winter. They are small plovers and breed in monogamous pairs. Their nests are a shallow scrape in the gravel, lined with many small stones, so they are very hard to spot, and when incubating, they rely on camouflage to avoid detection. Each pair defends a territory and nests alone. The chicks are guarded by one or both parents during at least their first three weeks of life.

Kahū/swamp harriers and karoro / black-backed gulls are natural predators. If camouflage doesn’t work, wrybill can use distraction – pretending to have a broken wing to lead predators away. However, that’s not a great strategy against introduced predators like feral cats, stoats, ferrets and hedgehogs.

Braided river birds are also very vulnerable to flooding. What is amazing is that they have evolved to produce multiple clutches of eggs as a way to cope with losing their nests.

Photo credit : Philip Guilford, George Empson, Liz Brown

Tuke / Rock wren

Population

Unknown

Conservation Status

Threatened – nationally endangered

How are we protecting them?

Along with Predator Free Aoraki, we have extended trapping into alpine areas. In 2021, nine sites in the Te Manahuna Aoraki project area were surveyed and tuke were still persisting in all of the sites.

The tuke / rock wren is a small, reclusive alpine bird, found along the Southern Alps and Kahurangi National Park. It has a very high pitched call that not everyone can hear.

Of the half dozen New Zealand wrens known to have existed, all but two are extinct – only the tuke / rock wren and the rifleman / titipounamu still exist.

They live above the tree line and it’s unknown how they survive the harsh climate all year round, but it’s likely they forage on rocky bluffs where snow has not collected in winter and among large boulder fields.

Males are more vibrant, and the female is a paler brown. They are poor fliers, and their habit of nesting in holes on the ground makes them easy prey for stoats. They can become extinct quite quickly, site by site.

It is thought climate change will affect rock wrens in the future. As temperatures warm, they may encounter potential predators higher in the mountains.

Photos : Jemma Welch, Chad Cottle, Dean Nelson

Tarapirohe / Black-fronted tern

Population

5-10,000

Conservation Status

Threatened – nationally endangered

How are we protecting them?

A Lincoln University Master’s student has attached GPS trackers to black fronted terns in the project area to reveal their daily movements and see how far they travel from their breeding colonies. Increased predator control is also helping their survival.

Unlike most terns which are seabirds, the tarapirohe/black-fronted tern lives and breeds inland, only visiting the coast to feed in autumn and winter.

Breeding is a risky business on braided riverbeds as they nest in colonies on open shingle – this gives the parents a better chance to notice predators and try and scare them away by diving, calling loudly and even flicking poop at them. The eggs and chicks are well camouflaged, but unlike other species young terns stay near the nest as they rely on parents bringing them food until the can fly and hunt themselves.

As well as introduced stoats, ferrets, feral cats and hedgehogs, kāhu/swamp harriers and karoro/black-backed gulls are also natural predators. Habitat loss and disturbance by humans also impact their survival.

During breeding season they feed on mayflies and stoneflies or small fish and earthworms, skinks and grass grub larvae. On the coast they enjoy planktonic crustaceans.

Photos : Renke Lunken, Charlotte Patterson

Tarāpuka / Black-billed gull

How are we protecting them?

Te Manahuna Aoraki Project’s increased predator control networks in the braided river systems will help the survival of the black-billed gull. Our 2021 monitoring observed one colony that hatched over 300 chicks.

The Tarāpuka / black-billed gull is found only in New Zealand, and is one of the most threatened gull species in the world.

They mainly breed in South Island braided riverbeds, although there are scattered colonies in the North Island. They prefer the coast in winter, so you will spot them along the coastline and estuaries.

You can identify the tarāpuka from the more common red-billed gull because it is more slender, and has a longer, black bill (hardly surprising, the red-billed gull has a red bill). Black-billed gulls are less likely to be found in towns and cities than other gulls, and are less commonly seen scavanging for food. However, in 2019 the tarāpuka became famous when around 300 were found nesting in an abandoned building in Christchurch.

Breeding on a riverbed is a risky business. Many tarāpuka eggs and chicks don’t survive, as they are easy pickings for predators like hedgehogs, stoats, ferrets and feral cats. While they do have good camouflage, black-billed gulls are also targetted by kāhu/swamp harriers and karoro/Southern black-backed gulls. They have to cope with floods too, so they have adapted to renest if they lose chicks or eggs.

Photos : Julia Gibson

Kāmana / Australasian crested grebe

How are we protecting them?

DOC and the Lake Alexandrina Conservation Trust have increased trapping around the lakes to better protect the birds.

With their distinctive black double crest and bright chestnut and black cheek frills, crested grebe are striking birds.

They live on lakes and use vegetation along the lake margins for nesting and shelter from rough weather. They are unusual, as they spend very little time on land. They attach their floating nests to underwater vegetation and carry their chicks on their backs when they are very little.

While they are found on every continent in the world numbers are declining in New Zealand because of introduced predators like stoats, ferrets and feral cats. Habitat loss through the drainage of wetlands and establishment of hydro schemes is also a factor. DOC and volunteers have been monitoring kāmana/Australasian crested grebe in two lakes in the project area.

In 2021 and 22, 35-40 of the birds were spotted nesting on the outlet stream between Lake Alexandrina and Lake McGregor. This is highly unusual behaviour as the birds don’t normally nest close together, and it is quite a spectacle.

Tūturiwhatu / Banded dotterel

How are we protecting them?

Banded dotterels are a small plover found throughout New Zealand. The ones that breed in the South Island high country migrate the furthest in summer –1600km or more to Tasmania and south-eastern mainland Australia, or to northern New Zealand.

They lay their eggs between August and November in shallow scrapes in gravel, or sand. The eggs and birds are incredibly well camouflaged, so it’s easy to overlook them, which is their main defence from predators. However, this also leaves them vulnerable to introduced predators, who use scent to track down their prey, and being run over by vehicles like quads or 4WDs on the river banks.

The broad chestnut breast band that banded dotterels are known for is actually the male breeding plumage. At other times they are plain brown above and mainly white below.

Kea

How are we helping them?

Increased pest control in alpine areas of the Te Manahuna Aoraki Project area will help kea survival. Our multi-pest elimination trial in the Malte Brun will also be an opportunity to find the best way to remove predators in kea habitat.

Named by Māori for the sound of their call (kee-ee-aa-aa), kea are a taonga species and one of the most intelligent birds on the planet. Studies have found kea can judge probability in the same way as infants or great apes. They are very curious, attracted to people and known for causing a stir in carparks or camping grounds where they are notorious for destroying property. They love tinkering and a kea reportedly once managed to lock a mountaineer in the toilet at Mueller hut. Their curiosity can be a problem. Traps in kea habitat have to be kea-proofed. Extra-long screws have to be used to secure the traps, so the kea can’t prise them open and get tangled in the devices.

Kea eat a wide range of plant and animal matter. They are particularly vulnerable to stoats and feral cats because they nest in holes in the ground. While they are sturdy birds they’re not fighters – they freeze and rely on camouflage. They benefit from pest control with monitoring showing that without control their breeding success rate is about 40% but this goes up to about 70% after trapping or aerial pest control. Unfortunately, studies have shown that kea in areas where they are fed regularly are more at risk from aerial pest control. Research has led to a better understanding of how to minimise the risk to kea from pest control.

Buildings with lead nails and flashing are also a problem. Lead is attractive to kea because it has a sweet taste to them, and this results in lead poisoning.

Kakī / Black stilt

Population

170

Conservation Status

Threatened. Nationally critical

How are we protecting them?

Te Manahuna Aoraki has increased DOC and Project River Recovery’s predator control from the Tasman to also include the Cass, Godley and Macaulay river valleys – trapping networks now cover 80% of the kakī range.

With their distinctive long pink legs and elegant black plumage, the kakī / black stilt looks graceful and delicate. But these birds are tough.

Kakī used to be common throughout New Zealand, but are now only found in the Mackenzie and Waitaki basins. They live in an extreme environment, in the summer temperatures can reach 40°C, while in winter their feathers can freeze in -20 temperatures.

While other riverbed birds migrate, kakī stay in the braided rivers and surrounding farmland all year round, where they are vulnerable to introduced predators like stoats and feral cats.

In 1981, the wild population was reduced to only 23 birds. Numbers have now increased to 170 adults living in the wild, thanks to the work of DOC’s Kakī Recovery Programme and others like the Isaac Conservation and Wildlife Trust.

Re:Wild has funded an aviary and brooder to help boost the kakī population and landowners of Te Manahuna Aoraki assist by helping locate nests and allowing trapping networks on their land.

The best places to view kakī are along the Takapō / Tekapo lakeshore, along the east side of Lake Pukaki, or the Tasman Delta near the Glentanner Park Centre and Lake Poaka.

FISH

Upland long-jaw galaxias

Conservation Status

Threatened - Nationally vulnerable

How we are helping this species?

Rūnaka from Arowhenua, Moeraki and Waihao are leading a native fish protection project in Fork Steam.

A skilled iwi team have electric fished the true left, or east, of the stream and its tributaries, removing invasive trout and returning them to the waterway below a weir that acts as a barrier to stop them returning.

This project builds on work by DOC and ECan which saw trout removed from the true right of Fork Stream, and is a great example of collaboration between Nga Rūnuka, Te Manahuna Aoraki, DOC, ECan, New Zealand Defence Force and Glenmore Station.

One of New Zealand’s largest populations of Upland long-jaw galaxias Galaxias prognathus ‘aff. Waitaki’ is found in the project area at Fork Stream which also includes the site of the rūnaka’s native fish protection project.

The name long-jaw is a clue as to how to recognise it – it has a long protruding lower jaw. It is a slender, elongated, small fish that is usually creamish-grey with bold greenish-grey blotches and spots on back and sides. Galaxiids are a group of Southern Hemisphere fish that don’t have scales and, a dorsal fin located very close to the tail.

Five species of galaxias are migratory and the rest have diversified to live their lives in freshwater. The upland long-jaw likes the cooler waters of mountain spring streams, many above the post-glacial lakes.

Upland long-jaw galaxias eat invertebrates and mostly feed at night. They like good shade along the river bank. Not only do introduced trout compete with native fish for habitat and food, they also feed on the native galaxias. The cool springs in the Fork Stream valley system provide the conditions in which they are able to thrive.

Photos : Wikimedia Commons credit Simon Howard and Simon Elkington

Bignose galaxias

Conservation Status

Threatened - Nationally vulnerable

How we are helping this species?

Rūnaka from Arowhenua, Moeraki and Waihao are leading a native fish protection project in Fork Steam.

A skilled iwi team have electric fished the true left, or east, of the stream and its tributaries, removing invasive trout and returning them to the waterway below a weir that acts as a barrier to stop them returning.

This project builds on work by DOC and ECan which saw trout removed from the true right of Fork Stream, and is a great example of collaboration between Nga Rūnuka, Te Manahuna Aoraki, DOC, ECan, New Zealand Defence Force and Glenmore Station.

Twenty-three species of galaxiids have been discovered in New Zealand, and before non-native species like trout were introduced they were the dominant freshwater fish family.

Like all non-migratory galaxias, bignose live in freshwater their whole lives and mostly feed at night on invertebrates. They are found in small spring and wetland-fed tributaries and like good cover along the stream edges. Bignose are unique to the upper Waitaki River system.

Bignose are a golden colour, with darker mottled markings. They may have a big nose but they are a small fish that usually don’t grow any longer than 80mm. Their biggest threat is introduced fish like trout – not only do they eat galaxias, but they also compete with the native fish for food.

When native fish are threatened they will often move to more marginal habitat to find refuge rather than compete and be eaten. This is evident in areas of Fork Stream where trout are abundant. Where they have not been driven to local extinction, once trout are removed bignose become bolder and expand back into their niche.

Photos : Wikimedia Commons credit Simon Howard, Simon Elkington and Dr Robert McDowall

INSECTS

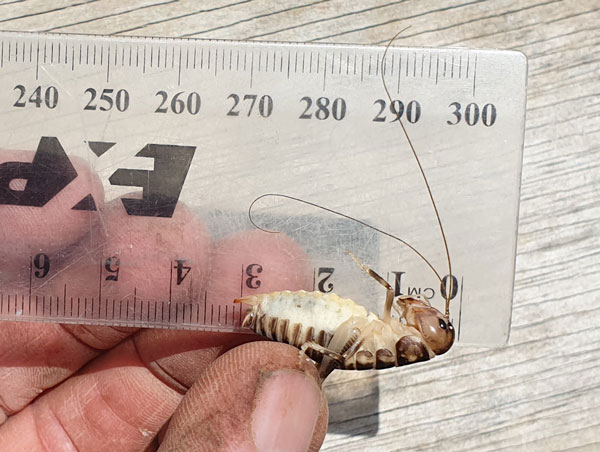

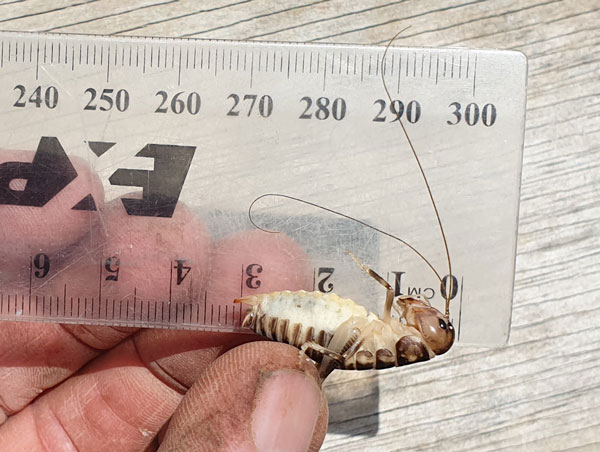

Robust grasshopper

Conservation Status

Nationally endangered

How are we helping them?

The project has built what is thought to be the world’s first predator-exclusion fence for insects to protect and study the robust grasshopper.

Read more about this insect in our Protection section

Robust grasshoppers (Brachaspis robustus) look like little grey tanks, short and squat with beautiful grey or rusty red ridges. Their colouring make them hard to spot as they blend in with their surroundings.

They are endangered and normally only found in the open gravel riverbeds of the Mackenzie Basin. However, one of the largest known populations is found on a 3.5km long unused gravel road built during the construction of the Tekapo canal in the 1970s. It’s not know if the population extended naturally from the nearby river or if it established as a result of being moved during the canal construction.

At 38-42mm, adult females are almost twice the size of a male. As a first defence to predators they freeze, which isn’t much help when you are up against predators like mice, rats, stoats, feral cats, hedgehogs and ferrets. Robust grasshoppers are herbivores and they are particularly fond of dandelions.

The lifespan of B robustus is approximately two years. Eggs are laid in summer and they overwinter, often surviving temperatures well below zero, before hatching into nymphs the following summer. The nymphs overwinter to reach maturity the next summer and lay their own eggs.

Photos : Tara Murray, Jennifer Schori

Alpine grasshopper

Conservation Status

Not threatened

How are we helping them?

Predator control will help grasshoppers and our macro invertebrate monitoring will allow us to learn more about this species. While it is not threatened we have included it in our monitoring as it is active during the day.

The Alpine grasshopper (Sigaus australis) is New Zealand’s most common alpine grasshopper. It can be found in the southern half of the South Island above the tree line although they prefer tussock grasslands between 1300 and 1700 m.

Like all of New Zealand sub-alpine and alpine grasshoppers S. australis has a 2 or 3 year life cycle. It is a relatively large grasshopper at 26mm and they can survive the cold by freezing solid at any life stage.

The alpine grasshopper is usually olive green, brown, or grey, with light coloured stripes running down each side. This grasshopper is a good jumper but while it does have tiny wings (between 2-4mm) like most of New Zealand’s grasshoppers it is flightless.

Amazingly, grasshoppers can eat half of their body weight in plants every day making them an important native herbivore in alpine ecosystems.

Photos : Inga Booiman, Tara Murray, Wikimedia commons NZ Snowman

Alpine scree wētā

Conservation Status

Not threatened

How are we helping them?

Te Manahuna Aoraki is monitoring invertebrates over three years to get a better understanding of how widespread this species is. This information will help us design the best predator control to protect wētā.

The Alpine scree wētā (Deinacrida connectens) is only found in the South Island and is the most widespread of eleven species of giant wētā. The scre wētā is much less agressive than tree wētās. When disturbed, it will either remain motionless or attempt to run away. If they need to defend themselves, they will raise their legs in a threatening posture and produce soft sounds. Luckily they live in the alpine zone which is traditionally above rat level, as being large and unaggressive aren’t characteristics that would protect them from predators. If rats move higher into the mountains as a result of climate change the alpine scree wētā could quickly become threatened.Scree wētā can have vastly different colouring, from mostly black bodies to a mix of red, grey and olive. Duringthe day, they stay under rocks and in crevices of scree slopes. During the night, they come out of cover to feed on plants like lichens, herbs and shrubs.

Tekapo wētā

Conservation Status

Nationally critical

How are we helping them?

It’s not yet clear whether the wētā has benefited from living in the pest-free environment of our robust grasshopper pest free enclosure. Hedgehogs are known to enjoy feeding on wētā so over the 2021/22 summer an Otago University student will study the wētā inside and outside the fence. Early indications are the Tekapo wētā may be more common than previously thought as the species was also detected in two other sites by our invertebrate monitoring teams.

The Tekapo ground wētā is thought to be extremely rare, and lives on river margins near Takapō/Tekapo. It burrows in silty soils and usually prefers to live on river terraces. But in times of severe flooding it’s burrows can be covered with water and silt, making them very vunerable. Weeds are also a problem for this insect as they bind up the soil making it hard for them to burrow. Ideally they need quite specific conditions, preferring a mix of silt and gravel. Off-road vehicles can disturb their burrows as well. To the excitement of scientists, a relatively large population of the Tekapo ground wētā was found in 2021 when DOC staff were removing skinks from a pest-free enclosure at Paterson’s Terrace.

Mountain stone wētā

Conservation Status

Not considered at risk

How are we helping them?

Our alpine predator control will benefit this species. We are also monitoring wētā in the project area.

This incredible insect has the ability to survive being frozen!

As a species, mountain stone wētā have been around for 60-80 million years. They live high in the Southern Alps and are exposed to high winds and low temperatures all year round. In winter it can survive down to -10°C with up to 80% of its body frozen. It has developed special proteins that prevent ice crystals forming inside its cells – the largest known insect that can do this. It can survive harsh winter conditions in this suspended animation. In spring, it thaws out, returning to the land of the living.

This wētā is vulnerable to native predators like ruru/morepork, as its defence mechanism is to play dead and vomit at the same time. However, as temperatures increase with climate change, more introduced predators are pushing up into the alpine zone.

Our alpine predator control will benefit this species.

LIZARDS

Alpine rock skink

Conservation Status

Threatened-Nationally vulnerable

How we are helping this species?

Because of its size this skink is vulnerable to predators like stoats and feral cats so our predator control will help the survival of this species.

This species (Oligosoma) was first discovered in 2018 in Northern Otago and until now hasn’t been seen in Te Manahuna. Our lizard monitoring team think they discovered some in the project area in 2021 and if that’s confirmed when we have the results of genetic testing this find will expand the range of the alpine rock skink.

It’s an active, beautifully coloured rock-dwelling skink which is usually around 89mm in length which is big in the lizard world. They live in high-elevation scree and boulder fields and eat invertebrates and the fruits of native shrubs. There’s still a lot to learn about this skink.

Photos : Sam Turner, Julia Gibson

Jewelled gecko

Conservation Status

At Risk – Declining

How are we helping this species?

Pest and invasive weed control will help the jewelled gecko.

The jewelled gecko lives in trees (arboreal) and is a diurnal species which means it is active during the day. It can live in a wide range of tree and shrub species including matagouri and loves to bask in the sun on top of vegetation.

It is a species that can live for over 30 years. While they can be found all over the South Island, loss of forest and shrubland means distribution can be a bit patchy in the Mackenzie Basin. Its name refers to the typical pattern of diamonds on its back. Depending on their location and range their colouring can be quite different – males in the project area can be an even mixture of green and grey/brown, while the females appear to be green in base colour.

The jewelled gecko eats a wide variety of insects and moths. It also eats berries and, more rarely, nectar. Like other lizards it is an important pollinator and disperser of seeds.

Photos : David Sarar, Aalbert Rebergen, Antje Leseberg

Long-toed skink

Conservation Status

Nationally vulnerable

How are we helping this species?

Predator and invasive weed control is helping the long-toed skink. As not much is known about this species our lizard monitoring will also provide valuable information.

Oligosoma longipes

Even the scientific name, Oligosoma longipes, means long toed so there is no denying what makes this skink a little different. It also has a long tail but is a small to medium skink only growing up to 67mm long.

This species was only discovered in 1997 and is found in a few places in the upper reaches of Canterbury and southern Marlborough. It lives in dry rocky areas, rock piles and tussock grassland.

While the long tail and toes are its most distinctive features you can also identify it through its colouring – its back is grey-brown, with spots and flecks and a darker strip down the middle.

Like all lizards the long-toed skink is cold-blooded, it needs warmth to digest food and is commonly seen basking in the sun on warm rocks.

Photos : Marieke Lettink, Julia Gibson, Simone Smits

Scree skink

Conservation Status

Threatened – nationally vulnerable

How we are helping the scree skink?

Invasive weed and predator control will help the scree skink.

Scientific name – Oligosoma waimatense

Size matters when it comes to scree skinks – they are one of our largest skinks, with a tail that is longer than their body. They also have very long toes to help them move around their unstable habitat.

Home is rocky scree, boulder fields or river beds. The scree skink will actually dive into water to escape capture and they are very alert – they will see you before you see them. They differ in colour from grey to brown but are usually very heavily flecked.

This species is found from South Marlborough to North Otago in sub-alpine areas. Because they can be found in stream beds flooding can devastate a scree skink population. Mammalian predators and weeds also impact this species.

Photos : Samuel Purdie, Julia Gibson

Southern grass skink

Conservation Status

At Risk – Declining

How we are helping them?

Increased trapping will help these skinks. Lizard monitoring is also providing baseline knowledge about how these lizards respond to landscape-scale predator control, and how we can better protect them.

Scientific name: Oligosoma aff. polychroma Clade 5

If you see a disappearing flash of brown it’s likely to be either a Southern grass skink or the more common McCanns skink.

Southern grass skinks are only found east of the main divide from Canterbury to Rakiura/Stewart Island. It has a dark tan band down the centre of its back and two cream stripes along its sides, and reaches about 80mm in length.

Until 2008 it was considered part of a widespread species called the “common skink” but it’s now known as the Southern grass skink.

They can have up to six babies at a time which is handy as this species only lives four to six years. In the project area you will find it around shrub, tussock lands or boulder slopes. It can use the burrows of invertebrates like worms, spiders and wētā to retreat from predators and to escape the winter cold.

Southern grass skinks eat small invertebrates such as spiders, insects, molluscs and worms, and they actively pursue their prey. They supplement this with some soft fruit including berries.

Photos Julia Gibson

Southern Alps gecko

Conservation Status

Declining

How are we supporting them?

Increased predator control should help the Southern Alps gecko population grow.

Southern Alps gecko (Woodworthia sp. ‘Southern Alps’), or mokomoko are part of the ‘common gecko’ group and found throughout the Eastern South Island high country. They are the most common lizard our monitoring has found – appearing at all our monitoring sites.

The common gecko has been separated into over ten different species. In the project area they can vary in colour and body size between individual populations. They are usually dark, or silvery grey and can be from 55-72mm long.

They are generally nocturnal but you do sometimes see them basking in daylight or under rocks on stable scree slopes and outcrops in the sub-alpine areas. The tend to live at lower elevations between mountain ranges but our monitoring team found one at 1900 m in the Malte Brun range – they highest they have ever been found.

Like all gecko they grow a new skin and shed the old one (called sloughing) each year. They can also grow new tails, and while unusual sometime the tail grows back forked like in one of these photos.

Photos Julia Gibson and Mahina Walle

McCann’s skink

Conservation Status

Not threatened

How are we supporting them?

Increased trapping in alpine and braided river areas will help these skinks. Te Manahuna Aoraki Project began monitoring lizards in 2020 which will help our understanding of this lizard.

The McCann’s skink (Oligosoma (South Island) species) is a small skink that is common throughout the Mackenzie Basin – if you see a skink disappearing into the grass, it is likely to be this guy.

McCann’s skinks live in open, dry, rocky areas including braided riverbeds and montane grasslands, right up into subalpine regions. They are recognisable by a prominent checker-board pattern on their back. They can live up to eight years and are somewhat solitary. You can spot them during the day, sun-basking and hunting.

Tasty meals for McCann’s skinks are spiders, millipedes, beetles, larvae, and flies. They also eat small fruit and flower nectar.

Introduced predators like hedgehogs are the skink’s enemies. Back in 2009, a study examined 158 hedgehog stomach remains and found that 21% contained lizards, many of which were McCann’s skinks (Spitzen et al.).

Skinks will drop their tail if they are threatened as a way to distract predators. They can regrow the tail, but sometimes they regrow with slightly different patterns or colours. The tails are a good fat repository and will help them survive the winter, so shedding them is a last resort.

Mackenzie skink

Conservation Status

Nationally vulnerable

How are we protecting them?

The project has been monitoring lizards since 2020, so we can understand how many we have in the project area, and how they respond to predator control.

The Mackenzie skink (Oligosoma (South Island) species) is closely related to three other spotted skink species – the Canterbury spotted, northern spotted, and Marlborough spotted skinks. They are only found in the Mackenzie Basin, with its southern limit being Lake Pukaki.

It’s a large and often beautifully coloured skink, sporting various shades of grey-green, brown, or olive green, and stripes that break up on the tail. You can tell it apart from other skinks of the Oligosoma species by the lack of ocelli (eye-like markings) on the tail.

Mackenzie skinks are shy – they are more likely to see you and disappear before you have a chance to see them. They are avid sunbaskers, and prefer open/sunny areas such as tussock grassland, rocks, and scree slopes. When not basking or foraging, Mackenzie skinks will hide under rocks, logs, or in dense vegetation such as thick grass and complex shrubs.

They are becoming increasingly rare due to predation by introduced predators like rats, stoats, hedgehogs and feral cats. Like other New Zealand skinks, they eat a wide range of bugs and the berries, fruit and nectar of native plants.

If threatened, skinks will drop their tail. The ditched tail then wriggles for a short time to allow the animal a chance to get away. The skink can then regrow its tail, though with slightly different colours/patterning.

PLANTS

Mount Cook buttercup

Conservation Status

Not threatened

How we are helping this species

Buttercups are very tasty to browsers so our pest elimination in Aoraki Mount Cook National Park will provide an environment where the Mount Cook buttercup can thrive without pressure.

One of New Zealand’s most well-known alpine plants the Mount Cook buttercup (Ranunculus lyallii) can grow over a metre tall. It is particularly striking when growing in large numbers with its white flowers and glossy leaves which can grow larger than the size of your hand.

The cup-like leaves can be a trampers friend as they often hold water after a rainfall. Like others in the buttercup family it has developed a clever way to help its survival in the harsh alpine environment. Plants have stomates or pores in their leaves which let water in and out. Most plants have their stomates on the cooler, shaded underside of the leaf so they are less prone to drying out. But as the Mount Cook buttercup often grows among rocks which heat up during the day it has evolved to have stomates on both sides of its leaves.

It grows in sub-alpine to alpine herb fields and the side of creeks in the South Island mountains from 700m to 1500m in altitude. The Mount Cook buttercup flowers between October and January.

It’s Latin name (Ranunculus lyallii) comes from ranunculus, meaning little frog which probably refers to its typical marshy habitat. Lyallii refers to David Lyall a 19th century naturalist and surgeon with the Royal Navy. When Lyall first discovered the plant in the mid 1800s he only collected the leaves which resembled a lily so the plant was incorrectly known as the Mount Cook lily. A decade later it was identified as a buttercup when Sir Julius von Haast and Dr Andrew Sinclair collected flowering specimens.

Photo : Sian Reynolds, Wikimedia Commons Bernard Spragg

Common broom / mākaka

Conservation Status

Not threatened

How we are helping this species

Mākaka is a native that tends to be heavily browsed when rabbits and hares are around so pest control will help it. Because of its ability to grow quickly it is the perfect species to help us understand the impact of browsers and its’ ability to grow back so the project is monitoring mākaka on the Tasman riverbed.

As the name suggests mākaka is a relatively common shrub or small tree that is found throughout New Zealand apart from the deep south. Although in Te Manahuna / the Mackenzie Basin it is less common than the other shrubby “desert’ broom (Carmichaelia petriei).

It thrives on river terraces, rock outcrops, stream banks, tussock grassland and on the edge of swamps. It is a hardy fast growing species which has flattened stems instead of leaves to catch the sunlight.

From October to February it has pretty purple and white flowers. Mākaka has yellow or red seed pods from November to May. These pods burst with the seed travelling short distances.

Te Manahuna Aoraki Project has tagged 90 mākaka on the Tasman riverbed. We will monitor these over four years to guage the impact rabbit control has on the species. This outcome monitoring is funded by Toitū Te Whenua Land Information New Zealand through its Jobs for Nature funding.

Photos : Dean Nelson

Dwarf broom

Conservation Status

Threatened - Nationally vulnerable

How we are helping this species?

Rabbit and weed control will help the dwarf broom survive in the project area.

Native broom are sometimes referred to as overlooked treasures with their wide range of interesting forms. They are mostly leafless and photosynthesise through their flattened stems which are called cladodes.

Dwarf broom’s scientific name is Carmichaelia nana; Camichael was a botanist, and nana means small. It forms dense, hard cushions of very low growing mats of leafless, bright orange branchlets and has small purple flowers between November and February.

It is endemic to New Zealand, and found in Marlborough, Canterbury and Otago, and also the Volcanic Plateau in the North Island. It is hardy and copes with full sun so is a good plant for dry conditions and recommended as the perfect addition to a rock garden.

Photos : Melissa Hutchison Wikimedia Commons, Robyn Janes

Desert broom

Conservation Status

At risk - Declining

How we are helping this species?

Hare and rabbit control will help the Desert broom.

Like most native brooms Carmichaelia petriei or desert broom is very hardy and well adapted to the conditions in Te Manahuna. It is endemic to New Zealand and found in the South Island as far north as the Mackenzie and as far south as Rakiura/Steward Island.

It’s a leafless shrub which can grow up to 2m tall and in the project area the leafless branches are usually yellowish at the tips (in less dry areas it can be greener). Desert broom has purple and white flowers, similar to the flowers of sweet peas. It flowers from November to January.

It has pea-like flowers because brooms belong to the legume family Fabaceae. Legumes fix nitrogen in the soil through special root nodules and therefore cope well in poorly developed soils. Seeds are produced from January to May and dispersed by the wind.

It’s scientific name is a nod to botanists Dugald Carmichael (a Scottish botanist who the Carmichaelia genus was named for) and Donald Petrie who was a Scottish born Otago botanist.

Photos : Wikimedia Commons John Barkla and Robyn Janes

Inland peppercress

Conservation Status

Threatened – Nationally Critical

How we are helping this species?

Rabbit and invasive weed control will help the survival of Lepidium solandri.

Inland pepper cress (Lepidum solandri) is a herb plant that is so rare there are less than 1000 plants known in the wild. It grows in tussock grassland and bare hillsides in Canterbury and Otago – in the project area these are often sites that are threatened by weeds and browsing animals.

It is an inland species of cress in the same genus of the equally rare coastal cress, Cook’s scurvy grass (Lepidium oleraceum), which Cook “collected by the boat load” to prevent scurvy in ship crews visiting New Zealand during the late 1700s and early 1800.

Lepidium means scale shaped and refers to the pods of tiny scented flowers which turn into small capsules on female plants. The flowers appear from September to January and can be green or white. Solandri refers to Swedish naturalist Daniel Carlsson Solander.

In addition to habitat loss, another reason Lepidium solandri is so rare and threatened is that it’s highly susceptible to a ‘fungus’ or rust infection (Albugo) carried by the white butterfly. The spread of albugo has been aided by intensive agricultural development adjoining dryland habitats.

Photos : Robyn Janes

Coral broom

Conservation Status

At Risk – Declining

How we are helping coral broom?

Our work to eliminate hares and rabbits will help the survival of coral broom.

Coral broom is an iconic desert plant that is perfectly adapted to its habitat. It is one of 23 species of native broom and is found in the dry montane and sub-alpine shrub and grasslands of the project area.

It was first recorded by Sir Julius von Haast in 1861. Coral broom is usually leafless and it has grooved stems and branches. As it grows in dry exposed areas the leafless branches carry out the functions of leaves and give protection from the heat of the midday sun.

While it can grow up to 2 metres tall, pests like hares, rabbits and other browsing animals usually prevent it from reaching this height. From December to January it has small pale pink, or white and purple flowers, and it fruits from March to May.

Photos Robyn Janes

Myosotis uniflora

Conservation Status

At Risk – Naturally Uncommon

How we are helping this species?

This plant occupies habitats that are vulnerable to weeds so the project’s invasive weed control should help it.

This striking cushion plant is found only on high-country shingle river beds from Canterbury to Central Otago.

Myosotis means mouse-eared and uniflora is single-flowered. It is unique from other Myosotis varieties because of its preference for the stony river beds and easily recognisable by the dark green cushions it forms and yellow flowers which appear from September to November.

Plants like these form cushions as a way to withstand the exposed harsh environments they live in, typically at high altitude. Their smooth, rounded surfaces deflect wind, and tight growth prevents cold winds from reaching the plant’s centre.

Photos Sam Staley

Pinātoro / New Zealand daphne

Conservation Status

Various threat categories

How are we helping these species?

The project’s invasive weed control will provide more habitat for pinātoro to flourish.

There are several species of the pretty mat forming shrub pimelea in the project area, some are threatened, while others more common. They are often hard to tell apart, not least because they can hybridise.

Pimelea prostrata is a common one in kettlehole margins and river beds, and is easily identified by its hairless leaves and its blueish colouring.

Pimelea pulvinaris is easily identified by its compact cushion form.

The other common ones include Pimelea oreophila and Pimelea sericeovillosa. They are more likely to be found in outwash terraces among short tussock grassland.

New Zealand daphne flowers abundantly in summer, with the small white flowers smelling strongly. After flowering it produces white berries that can be eaten but they are poisonous to livestock.

Photos Robyn Janes

Scree pea

Conservation Status

At Risk – Declining

How we are helping this species?

Our hare and possum control will reduce the browsing on the scree pea.

Scree pea, or Montigena novae-zelandiae grows in scree in the eastern Southern Alps between 800 and 1500m. Its genus Montigena, means Mountain Born. The other 51 species in the genus are found in Australia with only the scree pea endemic to New Zealand.

The scree pea pokes its head above ground in December, and it’s pretty pink and strongly scented flowers appear for a few weeks in January at which time it is vulnerable to hares and other browsers.

Yellow alpine buttercup

Conservation Status

At risk - recovering

How we are helping this species?

Hare control as part of our multi-species pest elimination will help alpine buttercups.

The rare yellow alpine buttercup is only found in rock fields in the central part of the Southern Alps, between Aoraki Mt Cook and Arthurs Pass National Park’s.

It may look delicate but it lives in harsh mountain environments and loves having its feet wet. It’s latin name ranunculus means little frog and it’s thought it refers to the marshy habitat the buttercup enjoys.

You will come acros the yellow alpine buttercup high in the mountains, often on cliff faces and permanently damp ledges near icefields and glaciers. They are hard to spot as their blue-grey leaves blend into the rock fields, but when they decide to reproduce it’s a different story with their large yellow flowers calling in pollinators. It is most easily recognised by those bright yellow flowers in January and February.

Photos Jane Godson

Matagouri

Conservation Status

At Risk – Declining

How we are helping Matagouri?

Matagouri faces competition from weeds like gorse and broom, so eliminating those weeds will give it more space to thrive. Possums also like the sweet sap of matagouri in early spring so controlling possums will give it more of a chance.

Matagouri/tūmatakuru, or wild Irishman as it is sometimes known, is a spiny tangled shrub with long thorns that is common in the project area.

It is a slow growing bush, and it’s thought some plants on undisturbed river terraces could be as old as 100 years. The thorns were used by early Māori as tattooing needles when no other materials were available. The spines can be several centimetres long and the flowers make very good honey. It can grow up to six metres high.

Matagouri is similar to plants like peas and beans, in that it has special micro-organisms on its roots that enable it to take nitrogen from the atmosphere. This ability to ‘fix nitrogen’ means it can live in relatively unhospitable habitats. It also benefits other plant species by enriching the soils around them.

Our Work

Find out more about our work to protect native species

Report a sighting

We’d love to know what you’ve seen in the area – email us now

Photo credits: